The Problem of Life and its Solution

"Look for it in your volition, my friend, — that is, in your desire and avoidance. Make it your goal never to fail in your desires or experience things you would rather avoid; try never to err in impulse and repulsion; aim to be perfect also in the practice of attention and withholding judgement."

Discourses, Epictetus

In the grand tapestry of existence, human beings are unique in their capacity for reason, dwelling within a rational universe. Within this rationality, the inescapable conundrum of human life surfaces: suffering. Over two millennia ago, the illustrious philosopher Epictetus astutely identified this pervasive human dilemma and offered a profound solution—one that I am eager to explore and put into practice.

Epictetus: The Stoic Sage

Epictetus (c. 55 – 135 CE) was born into the shackles of slavery within the vast Roman Empire. Yet, through relentless determination, he secured his freedom as a young man and embarked on a lifelong journey of Stoic philosophy. His teachings found their home in Rome, and he later founded his own school in Nicopolis, Greece, where he imparted Stoic wisdom until his passing.

The problem: Suffering and Our Misconceptions

Epictetus's core insight lies in our inability to differentiate between what lies within our control and what exists beyond it. Within our sphere of control are the realms of our thoughts, judgments, intentions, desires, and aversions—the intricate landscape of our inner world, governed by our volition. Conversely, the external world, encompassing our bodies, possessions, relationships, wealth, fame, and reputation, is largely subject to forces beyond our influence. Epictetus even went as far as to declare that our bodies are but cleverly fashioned clay; what truly belongs to us are the powers of our impulses, desires, and aversions—the power to make wise use of impressions.

Yet, tragically, we frequently fixate on and attach ourselves to the externals—the very things beyond our control. Our bodies, possessions, families, friends, experiences, fame—all these fleeting aspects of existence hold our attention. Blaise Pascal, in the 17th century, aptly noted this human tendency: "We run heedlessly into the abyss after putting something in front of us to stop us from seeing it." We deceive ourselves by identifying with these ephemeral experiences, places, and people, even though we hold no true power over them. As Epictetus poignantly stated in his Discourses,

The more we value things outside our control; the less control we have

Epictetus, Discourses

To make matters worse, we often assume that external objects and circumstances are the most valuable things in life. We mistakenly believe that happiness is found outside of ourselves. Then, when the external world disappoints, we experience grief, fear, envy, desire, and anxiety. But Epictetus rejects the view that these emotions are imposed on us. Instead, we are responsible for our emotions, feelings, thoughts, and actions, and the circumstances of our lives are simply the arena in which we exercise our volition. Epictetus believed that we are nothing other than impressions, we act based on the impressions. He believed that impressions themselves are neutral and not inherently good or bad. It's our judgments and interpretations of these impressions that give them value. Confusing the internal world of our mind, over which we have control, with the external world, which we can only influence but not control, causes most suffering that we encounter.

The solution: Embracing Inner Mastery

The journey to ending suffering, according to Epictetus, begins with an unwavering focus on what we can control while relinquishing attachment to what we cannot—the externals. We possess the power to govern our judgments and interpretations of impressions. Although we cannot dictate external events or the impressions that emerge, we maintain the agency to choose our responses through our judgments. We must recognize that true well-being does not hinge upon the possession of external goods but rather upon the mastery of our internal states of mind.

Epictetus implores us to wage war against impressions. He calls us to scrutinize every impression before embracing or rejecting it, employing only those that withstand the test. In every situation, whether joyful or daunting, we must discern what is within our control and what lies beyond it. As Epictetus writes:

In the first place, do not allow yourself to be carried away by [the] intensity [of your impression]: but say, ‘Impression, wait for me a little. Let me see what you are, and what you represent. Let me test you.’ Then, afterwards, do not allow it to draw you on by picturing what may come next, for if you do, it will lead you wherever it pleases. But rather, you should introduce some fair and noble impression to replace it, and banish this base and sordid one.

Epictetus, Discourses

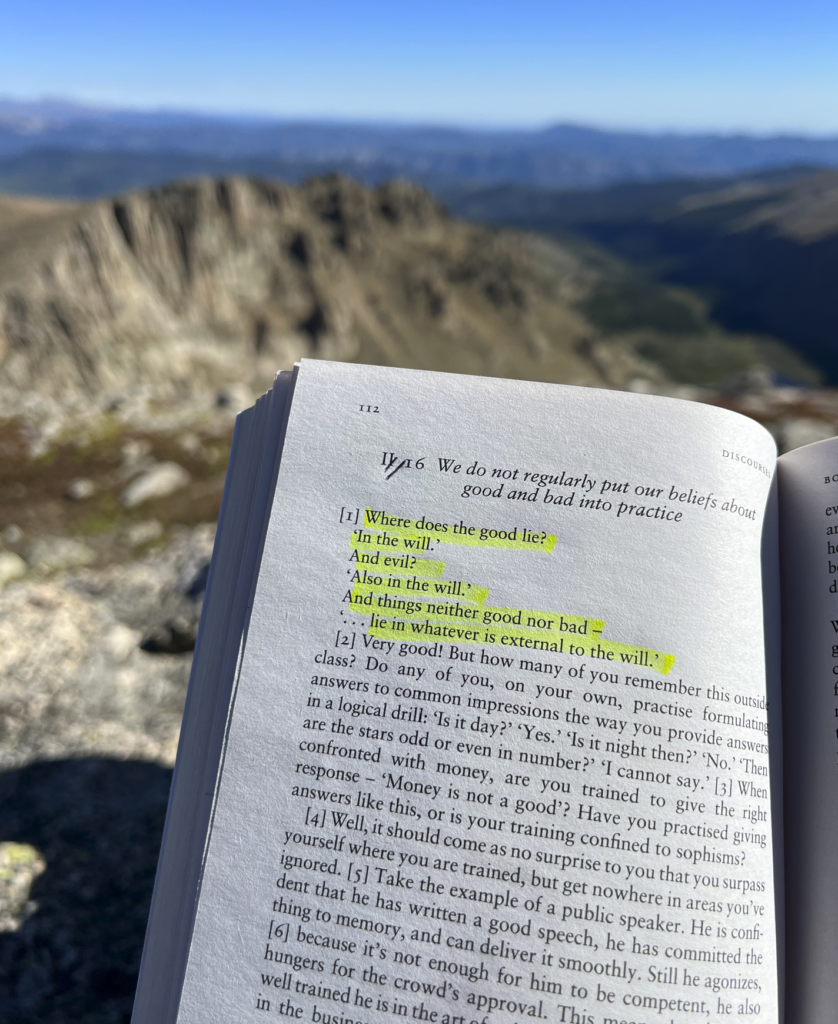

In Book II of Discourses, he wrote:

We aren't filled with the fear except by the things that are bad, and not by them either, as long as it is in our power to avoid them...… so, if external are neither good, nor bad, while everything within the sphere of choice is in our power and can not be taken away by anyone, or imposed on us without our compliance then what's left to be fearful about and what is there to suffer for?

Epictetus, Discourses

In other words, as long as we prioritize what is within our control—our inner world—suffering becomes an inconceivable notion.

Conclusion: The Path to Freedom and Fulfillment

In conclusion, I would like to include some profound thoughts of the father of modern philosophy, Rene Descartes, who extolled Epictetus's teachings.

My third maxim was to endeavor always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in things external to us, all wherein we fail of success is to be held, as regards us, absolutely impossible: and this single principle seemed to me sufficient to prevent me from desiring for the future anything which I could not obtain, and thus render me contented; for since our will naturally seeks those objects alone which the understanding represents as in some way possible of attainment, it is plain, that if we consider all external goods as equally beyond our power, we shall no more regret the absence of such goods as seem due to our birth, when deprived of them without any fault of ours, than our not possessing the kingdoms of China or Mexico, and thus making, so to speak, a virtue of necessity, we shall no more desire health in disease, or freedom in imprisonment, than we now do bodies incorruptible as diamonds, or the wings of birds to fly with.

But I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and frequently repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and, amid suffering and poverty, enjoy a happiness which their gods might have envied.

For, occupied incessantly with the consideration of the limits prescribed to their power by nature, they became so entirely convinced that nothing was at their disposal except their own thoughts, that this conviction was of itself sufficient to prevent their entertaining any desire of other objects; and over their thoughts they acquired a sway so absolute, that they had some ground on this account for esteeming themselves more rich and more powerful, more free and more happy, than other men who, whatever be the favors heaped on them by nature and fortune, if destitute of this philosophy, can never command the realization of all their desires.

Descartes, 3rd part of Discourse on Method

Epictetus's counsel calls us to accept external events with equanimity, whether favorable or unfavorable, as we cannot change the past or alter the elements outside our control. Instead, we should focus our energies on what we can master—our thoughts and judgments. In doing so, we free ourselves from the fetters of external circumstances and others' opinions. Our inner strength and character become the bedrock of our well-being, and we transform from slaves to the whims of the world into sovereign masters of our own destiny.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.